My friend, Barb, said, ‘The IFLA Annual Conference

is in Wrocław,

Poland this year. Do you want to go?’ I’d never been in Poland,

nor did I know anything about Wrocław so I replied, ‘Of course!’ And off we

went on a rather unusual adventure. Wrocław has a history dating back a

thousand years and throughout that time has functioned as the capital of

Silesia and Lower Silesia; it’s still the capital of the Lower Silesian

Voivodeship (a governmental region similar to a county). Currently it’s considered one of the best

places in Europe to live because of the high level of art appreciation,

education, and international business; this is probably why it is the

fourth-largest city in Poland. While the part of the city that we saw was attractive,

I particularly liked the historic part. It’s very walkable with plenty of

things to see and do as well as good places to eat and shop.

Wrocław, which has several pronunciations depending on which country’s name you’re using, is a picturesque place on the banks of the River Oder.

The variety of names comes

from it being a part of Germany, Czech Republic, Bohemia, Prussia, and Poland. It’s

surrounded, once you’re out of the city, by small rolling hills and farmland

that sprout tiny hamlets every so often, reminding me a bit of what the English

countryside would look like if it didn’t have all of the hedgerows. In each of

the little towns we passed were churches with architecture that ranged from

just better than homely to grand edifices. One of our guides said that many of

these places of worship were constructed in memory of a person or family, and

that the people living in the towns may have gotten together to build the

church; this was supposed to explain why there are so many churches in this

part of Poland.

Wrocław's population is predominantly Roman Catholic but its religious

heritage comes from almost all of the religions and

cultures found in Europe. In the oldest part of the city is Ostrów Tumski,

Cathedral Island, on which is located Wrocław

Cathedral. One of the key words used to describe the church through the

centuries is ‘destroyed’. This grand edifice, dedicated to Saint John the

Baptist, was originally built in the mid-10th century; this seems

odd timing to me since the diocese wasn’t founded until 1000 (the beginning of

the 11th century). The church is described as Gothic with Neo-Gothic

additions, but it was originally a fieldstone building that was destroyed by invading troops in about

1039. A Romanesque-style church replaced it, but that was destroyed by Mongol troops. The original Gothic ‘replacement’ was

constructed during in the 12th century with the steeples added in

the 1300s. After a fire in the 1500s, the roof was restored in the Renaissance

style; but another fire destroyed

that in the 1700s. And it wasn’t until the late 1800s that the interior and

western side of the church were restored in the Neo-Gothic style. World War II destroyed about 70% of the building;

restoration wasn’t completed until 1991. Perhaps because of all of the

destruction and restoration, the stained glass windows are amazingly colorful

and vivid. While the external architecture seems to work together, the chapels have

their own unique styles that range from Gothic to Baroque to Neo-Classical. Evidently

information about Fatima is also a part of this Catholic Church as it was in

Budapest (see Being

in Budapest) at the synagogue; I’m always surprised and pleased at the

connections among religions.

As I wandered the streets, it became very apparent to me that the number of Catholic churches outnumbered any other variety of religious

establishments. Martin Luther’s Reformation had changed

many of the Catholic churches to Protestant, with the external building

remaining the same, but the icons and art taken down within the buildings. This

was quite apparent when we visited Saint

Mary Magdalene Church. It was established in the 13th century as a Catholic

church but became the site of the first Lutheran services held in the city in

1523. It is very plain on the inside, as fitting a Lutheran church, but the art

work can be seen in the Royal Palace City Museum; the first Lutheran leader

didn’t want the works destroyed, so he gave them to the city leaders. We went

into Saint Mary Magdalene to see a piano concert. The young man playing Chopin was okay, but he

didn’t use the pedal enough to keep the music from being muddy. Also, with the

acoustics as they were in a vaulted ceiling, the echoes didn’t enhance the

music, either. However, it was fun to go with friends and to be reminded that Chopin came

from Poland. There is an interesting legend involving the bridge connecting the

two towers. Although it is now one of the places from which tourists can view

the square, the Witches’ Bridge has shadows that are the souls of the girls who

seduced men but didn’t want to be married because they were afraid of

housekeeping. That legend made our group smile.

As with most countries under German rule, Jews were barely tolerated in

Wrocław. This bigotry goes back to the early

Catholicism leadership; one of the Bishops of the Catholic Church said that all

the Jews should be burned and that they shouldn’t be allowed back in the city

for 200 years. This Bishop is now a saint – hopefully that’s not his final

reward. In any case, that’s exactly what

happened and the Jewish population that eventually returned to the area lived

outside of the city. The White

Stork Synagogue was built in 1840 and Wrocław had the third largest Jewish

population in Germany. Surprisingly, although looted during the Nazi

occupation, the synagogue was not destroyed and rededicated in 2010; in 2014 it

celebrated the first ordination of four rabbis and three cantors since World

War II. The White Stork Synagogue, a Lutheran Church, a Roman Catholic Church,

and an Eastern Orthodox Church are located quite near each other in the Borough

of Four Temples. This religious tolerance is commemorated with a statue of a

young girl wearing the earth as a skirt.

One of the building complexes that drew me to it was the University of Wrocław. The oldest mention of a university in Wrocław is in the foundation deed of 1505; however politics and war kept the university

from being built

until 1702. It was then that Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I of the House of

Austria, King of Hungary and Bohemia signed the Aurea bulla fundationis

Universitatis Wratislaviensis into existence. The university was built before

that date and had functioned as a Jesuit school. Once it was endorsed by

Emperor Leopold I it functioned as a School of Philosophy and Catholic

Theology. In 1811, for political reasons, it was merged with the Protestant

Viadrina University, establishing five faculties: law, medicine, philosophy, Catholic

theology, and Protestant theology. There were also classes in linguistics,

mathematics, history, and science. By 1842, there was also a department of

Slavic Studies; an agricultural institute was established with classes in

veterinary chemistry, animal husbandry, and technology. Since the 1900s,

University of Wrocław has produced nine Nobel Prize winners

and is well known for its high quality of teaching. There is a museum that has

artifacts from the different schools as well as the regalia worn by the school

deans, provost, and president. I was a bit envious of their finery; all we ever

wore at the university in which I worked was a fancy hat and a bit of braid. For

all of its status, the ‘powers that be’ at the University don’t take themselves

too seriously. For a good chuckle, take a look at Lunch Time

and Beyond from the University website; they give some really interesting

advice to foreign students.

Within the University of Wrocław are the usual classrooms, and two

rooms that are of artistic significance, the Aula

Leopoldina and the Oratorium Marianum.

The Aula Leopoldinska is a representative Baroque aula designed and

built between 1728 and 1732. The room was named to honor Emperor Leopold I, the

founder of the university. The stucco decorations were made by Bavarian artist

Franz Mangoldt, the frescoes by Johann Christoph Handke, and wooden sculptures

by Krzysztof Hollandt. Although not as large as the Sistine Chapel, this room

is every bit as impressive, particularly since it is in a school rather than in

a church. I probably wouldn’t have been nearly as impressed with the room if I

had been listening to a long lecture while sitting on the hard wooden benches

that make up the furniture in the hall. At this time the room is being restored

and they seem to have it more than half completed. The Oratorium

Marianum echoes the décor of the Aula Leopoldinska, probably because it was

constructed at the same time and by the same people. This, however, is a music

hall rather than a lecture room, so the chairs are comfortable and there is a

raised stage at one end. It, too, has been restored, but from World War II

bombs. The restoration of the frescos was by Christoph Wetzel, a portrait

painter. Much like Michael de Angelo, he lay on a scaffold to work on the

ceiling, but unlike the Italian, Wetzel had numerous research materials from

which to work. Just at the east end of the University is the Church of the

Blessed Name of Jesus. The art within this structure mirrors that within the

University and that’s not surprising since the Jesuits built the church. It

actually rests on the site of the Piast castle, a portion of which can be seen

in the northern sacristy. One thing that surprised me about the frescos was the

inclusion of 18th-century representations of natives from Africa, the Americas,

Asia and Europe. The art work in this church was impressive.

|

| Wrocław city square |

Wrocław, which has several pronunciations depending on which country’s name you’re using, is a picturesque place on the banks of the River Oder.

|

| Rolling hills |

Wrocław's population is predominantly Roman Catholic but its religious

|

| Top L to R: Saint John the Baptist Cathedral, Pulpit Bottom L to R: Bright window, Exterior statues |

As I wandered the streets, it became very apparent to me that the number of Catholic churches outnumbered any other variety of religious

|

| Top L to R: St Mary Magdalene, Sanctuary Bottom L to R: Pulpit, Alter |

As with most countries under German rule, Jews were barely tolerated in

|

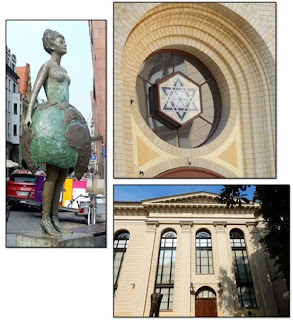

| Left: Religious Tolerance Right T to B: Star of David, Synagogue |

One of the building complexes that drew me to it was the University of Wrocław. The oldest mention of a university in Wrocław is in the foundation deed of 1505; however politics and war kept the university

|

| Top L to R: University facade, Nobel Prize, Student uniform Bottom L to R: Regalia, Light polarizer, Gneiss |

Within the University of Wrocław are the usual classrooms, and two

|

| Top L to R: Oratorium Marianum, Aula Leopoldinska Bottom L to R: Church of the Blessed Name of Jesus Altar, Ceiling frescoes |

Next week we’ll walk a bit more in Wrocław, then the week

after we’ll go to Auschwitz; once more back in Wrocław we’ll do some gnome

spotting and finally I’ll post a review of this trip. Stay tuned…

|

| Bricklayers' Gate and remnant of city wall |

©2017 NearNormal Design and

Production Studio - All rights including copyright of photographs and designs,

as well as intellectual rights are reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment